Art as a Game of Telephone

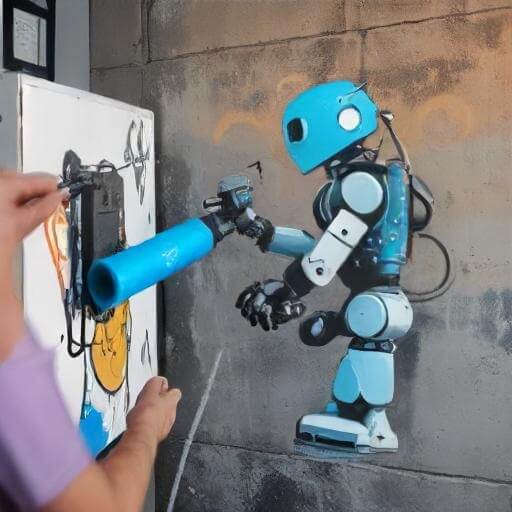

Exploring Individuality and Creativity in the Age of A.I.

An In-depth Opinion Piece Brilliantly Written

By Devin Barbour

In the classic game of telephone, players are tasked with passing a message from person to person until it reaches the original speaker. Unlike conventional games, there is technically no winner. Instead, the payoff comes from comparing the original message to the new version that has evolved from the passage of information. If you’ve ever played before, you’ll know that the more participants in a line, the higher the likelihood of the message becoming distorted. This noise in translation can result in a loss of the original meaning or a gain of new one in the process. On the other hand, playing with less participants helps to maintain the original source as there are less opportunities for the message to be drastically changed. I argue that this evolution of information as it is processed different times pervades the process of art making.

As Proust eloquently wrote, an artist’s “style”, “is in no way an embellishment, as certain people think; it is not even a question of technique; it is, like color with certain painters, a quality of vision, a revelation of a private universe which each one of us sees and which is not seen by others. The pleasure an artist gives us is to make us know an additional universe.”(In Search of Lost Time). These additional universes could be presented through prose, imagery, sculpture, etc, but the ultimate goal is to bring forth a phenomenological viewpoint which collectively hopes to make sense of the human condition. To share is a plea to be understood. Ultimately, art in this way can be described as a tool for bridging gaps of perception across time and space.

For a photographer, the camera is the medium/tool that is employed to capture a glimpse of what their eye is seeing. However, like all art forms, this process is governed by constraints both technical and creative. The choices of resolution, shutter speed, aperture, and focal length all contribute to a copy of the visual experience that is reminiscent of the subject, yet different in that it is an interpretation of what the artist wants you to see. This process could reflect someone playing the game telephone with one other person.

Assuming the first speaker is nature, and the message is the objective light that is reflected from the subject of the composition, the photographer and the process of them capturing the scene is the passage of the message to the second person in the game. That message, (or image in this example) is not a perfect replication of the original, but carries the weight of the photographer’s feelings and inner vision, thus becoming something uniquely human. If someone else were to then look at the image that was captured, they have become the third person in the equation.

Perhaps this process could feasibly be repeated infinitely, each time, conjuring and synthesizing their own world views with the stimulus of the image. How far this detracts from the original concept is up to interpretation. Each artistic medium comes with its own set of principles and constraints that limit how the artist is able to express their inner creative vision. In fact, that is what makes art interesting: each process of seeking to share an idea is a game of telephone, one that might be played over hours, days, or even years. Through this transcription of reality, an output is derived that is inevitably unique and hopefully true to the core intentions of the artist.

The question I am going to ask is whether or not this can be said about the use of generative AI as a medium for art creation. If we treat the original message as the input prompt for a large language model such as Chat GPT, the image or text output can look drastically different for numerous reasons. Ignoring the fact that the information itself needs to be encoded and passed through trillions of parameters which themselves could represent a scaled version of the telephone game. The output could be an image, essay, or even a paraphrased version of the original message. It could be argued that this expansion, compression, or maintenance of the size of the input is nothing drastically different from the creative process of turning a mental thought into an abstract object that bears resemblance to the original idea.

However, just because an art project is vast in scale does not mean that there was a lack of intention at every junction. Whether consciously aware of this or not, an artist makes decisions at every step of the creative process from deciding what paint, medium, subject or style to employ. Although increasingly complex prompts may capture such intentions, the artist is essentially passing the “creative torch” to another in which they are no longer the sole designer.

Many great artists usually have a specific audience in mind. The American writer Kurt

Vonnegut repeatedly said most of his stories were written with his late sister in mind. Jorge Luis Borges almost always dedicated his various essays and short stories to a particular person in his life. This acknowledgement of who they are speaking to is often the main driver of the creative vision and allows for clarity of theme. Perhaps the reason recent films have fallen flat is due to the extreme commercialization of Hollywood.

In an attempt to pander to all audiences, they often have the effect of catering to no one. Furthermore, while striving to squeeze out as much money as they can, film agencies often cut corners and increase their marketability by maximizing the scope of diversity. This isn’t to say that diversity is bad, but the way that it is employed often undermines the cultures it attempts to fit in.

If we apply the telephone metaphor to movie making, it could be said that the writer holds the original vision of the story in mind. If the writer is different from the director, then the movie goes through one extra filter of interpretation. This could be considered a good thing as the increased collaboration of multiple minds can result in a better product. Furthermore, both people have a shared goal of creating such a movie and are directly involved in the process in a symbiotic way. However, this can also break movies if both people have drastically different conceptions of how the final product ought to look. In this situation, having a cohesive almost dogmatic approach to the vision might ultimately end up with the most polished or believable look.

Quentin Tarantino might be one of the last examples of a director/writer that has near full creative control over his stories and thus is consistent in sharing with the world exactly what’s in his mind (whether we agree with his beliefs is up for debate). Regardless, his movies often maintain a cult following because they subvert movie genres and push the boundaries of how a story can be told. On the other hand, using chat gpt is akin to a monopolized production company imposing quotas and needs that ultimately destroy the agency of the creator. In other words, it is like a group of c-suite investors that know little of the product, only that they have programmed biases that hope to homogenize it to look like everything they’ve seen before.

Serialization and predictable content is safe, and safe means less risk for capitalists. Unfortunately, this usually leads to a stale product that doesn’t contribute anything drastically new or refreshing. Besides a few standouts like Guardians of the Galaxy or Deadpool, marvel movies on the whole have fallen victim to this assembly line process of movie making. Likewise, chat gpt art is safe. If you had a vision of some beautiful landscape that you wanted to portray, using generative AI may streamline that process, but it will ultimately be influenced by millions if not billions of other images of landscapes that will definitely create something “beautiful” just not what you may have intended in the first place.

When using a tool to do such a task, it is important that the tool itself does not muddle the vision of the creator. By muddle, I refer to a dilution of the intentions or perception of what that person is trying to convey. A tool is merely a conduit that effectively transposes the desired effect of the author. When such a tool begins to “think” for itself, or rather, adds layers of information processing or “thought” to the process of creation other than the creator, it leads to a disruption of cohesion and believability. It is also important to use anthropomorphic words like think and thought sparingly when talking about large language models. There is a necessary distinction between emulating language and comprehending it (Chinese Room thought experiment, Cole 2004).

At the moment, there is no clear evidence that LLMs such as chat gpt qualitatively “understand” the data that it is working with. Therefore, this puts them in a unique position of being highly advanced tools that may not be regarded as entities with agency or moral will, yet make and do things that seem plausibly human at the same time. Future developments of this technology are already raising philosophical questions on the ownership of generated art both by the data sourced and the notion of art authorship in general. Regardless if you believe that AI generated art is ontologically the same as one made with more traditional mediums, people have traditionally shown a preference for handmade products.

This association between handmade craftsmanship and quality is thought to be due to the “made with love” effect (Fuchs et al. 2015) and while possibly a psychological artifact with no tangible bearing, it has real implications for what humanity deems valuable. It is possible that future generative tools may reintroduce more comprehensive creative control, thus putting more power in the hands of the artists. However, as it stands, current market forces seem to be doing the opposite: reducing the process to a simple prompt output schema. After all, what’s more convenient than reducing a process that might have taken several hours, to a few seconds?

In conclusion, the evolution of information in the game of telephone offers a fitting metaphor for the process of art-making, where each layer of interpretation adds new meaning while potentially distancing the final product from the original vision. As art becomes more collaborative or involves more participants—whether in traditional mediums or through advanced tools like generative AI—the outcome becomes less about the artist’s pure intention and more about the collective impact of all the layers involved. While these tools may simplify the process and produce outputs that are visually or conceptually appealing, they come at a cost. The nuances of the artist’s individuality are exchanged for a synthesis influenced by millions of prior examples, ultimately creating something that is “beautiful” yet perhaps lacking the artist’s unique imprint.

As we move forward, the question of authorship and creative agency in AI-generated art becomes increasingly relevant. People have long valued the handmade, the crafted with intention, and this connection to the artist’s personal vision is what gives art its meaning. Although generative tools may evolve to grant creators more control, the current trend leans toward efficiency over individual expression, reducing the creative process to a prompt and an output. And while the convenience of such tools is undeniable, we must ask if the ease with which art is now made is also diminishing the very human labor and love that have historically given it its value.